August 26, 2021

Webinar Summary

On Thursday, August 26th, the G20 Interfaith Forum held a fourth webinar organized by the Anti-Racism Initiative, co-sponsored by the University of Winnipeg; the International Academy for Multicultural Cooperation; and the Fondazione per le scienze religiose (FSCIRE). Panelists included Afua Cooper, Professor of Black Studies at Dalhousie University; Dr. Samukele Hadebe, Fellow at the Chris Hani Institute in Johannesburg; and Dr. Adam Muller, Founding Member of the Global Consortium on Bigotry and Hate. Eliakim M. Sibanda, globally acclaimed advocate for human rights, peace, and justice, moderated the discussion.

Eliakim Sibanda began the discussion by highlighting the concept of structural racism, then inviting the panelists to “assist in unpacking this phenomenon.”

“Structural racism is an emotive and sensitive issue that always results in painful discussion. Investing in racism has provided people with power, resources, and opportunity. Racism has cash value. And because of that, it has shaped the structure of our everyday lives. It’s true that history cannot be un-lived. But if we face it with courage, it does not have to be lived again.”

Afua Cooper

Cooper focused her comments on criminal justice in Canada, citing statistics to emphasize the institutional racism that remains in the country, and why continuing racial hierarchies are doing so much damage to Canada’s black community.

“On the international stage, Canada is seen as a place of goodness and kindness where racism did not and does not exist. It’s often contrasted with the US and painted in an angelic light. But this forced denial of Canada’s anti-black racism renders our experiences as black Canadians invisible. Slavery has been excised from its historic chronicles and erased from its memory.”

Statistics Cooper cited referring to racism in Canada’s criminal justice system included the following:

- Black men in Halifax are street checked 9.2x more than white men, even though they only represent 1.8% of the Halifax community.

- Black people in Toronto (only 8% of the population) are nearly 20x as likely to be shot dead in a police interaction, and 6x more likely to be taken down by a police dog—hearkening back to the dogs used to hunt and catch escaped slaves.

- In the past two decades, the incarceration of Black people has increased by 70% in Canadian federal prisons, though Black people make up less than 3% of the population.

- In 2013, 44% of reported hate crimes in Canada were directed toward Black individuals.

She referred to a UN working group sent to Canada in 2017 to analyze racism in the country, who recommended that the Canadian government apologize for slavery, discontinue street checks, and address anti-Black racism in the criminal justice system, among other things.

“This issue of systemic racism, especially as it pertains to Black people, is beyond serious. We’ve seen how it intersects with thee COVID-19 situation in Canada. The two problems meet on the backs of Black people in this country, because we’re disproportionately affected by both of them.”

Dr. Samukele Hadebe

Hadebe focused his comments on manifestations of structural racism in the global South, specifically Africa.

“How can you talk about racism in areas where 99% of the population is black, and black people run their own lives and countries? The Black Lives Matter movement resonated with the global South because the experiences that were being shared echoed those of people struggling with lingering colonial structures in Africa.”

He said that though the countries in Southern Africa are now independent, they were without exception territorially carved by colonial Western powers, and the structural inequalities established through colonialism have yet to be addressed.

Examples Hadebe provided of these lingering structural inequalities include a general fear of police officers, government “shoot to kill” orders to police in civilian areas, and Black people providing cheap labor while the privileged few monopolize economic control of natural resources.

He said that the laws, education systems, and general ideologies of Southern Africa still support colonial hierarchical mindsets—often shifting race-based hierarchies to a stratification based on ethnicity that creates instability in governments. In the same vein, Hadebe noted that the countries themselves in Southern Africa follow the same center/periphery pattern that was established in colonial times: South Africa plays the role of the economic “center” while the surrounding countries provide cheap labor—creating negative stereotypes and xenophobia around migrant workers and the displaced which often lead to abuse, targeting, and victimization.

“We need to change the framework. We need a different template than that which was established in colonial times. Uprooting this racism cannot be left up to chance or individual choice. We must change the laws and policies that keep people disadvantaged. But it’s not in the habit of governments to change these things for altruistic purposes—so that’s where faith groups come in with their influence.”

Dr. Adam Muller

Muller took a broader view on the topic and looked at the “state of hate” at large in Canada. As part of his work with the Global Consortium on Bigotry and Hate, he holds “State of Global Hate” symposiums throughout the world that look at localized perspectives, statistics, and trends. Through his experiences and research, he said he’s found that media typically focuses on smaller, dramatic events rather than overall structural racism.

“We need to understand racism less as the exception and more as the rule. These dramatic representations of racism sometimes misdirect us, because they’re symptoms of our general history, not an aberration.”

Muller said that it’s very difficult to provide a snapshot of prejudice at large in any country—especially one as geographically large and diverse as Canada. Each area fosters different subcultures of hate—and in addition to that, since much of Canada’s population lives within 100 miles of the U.S. border, it’s difficult to overstate the influence of America’s perspective on race and race relations.

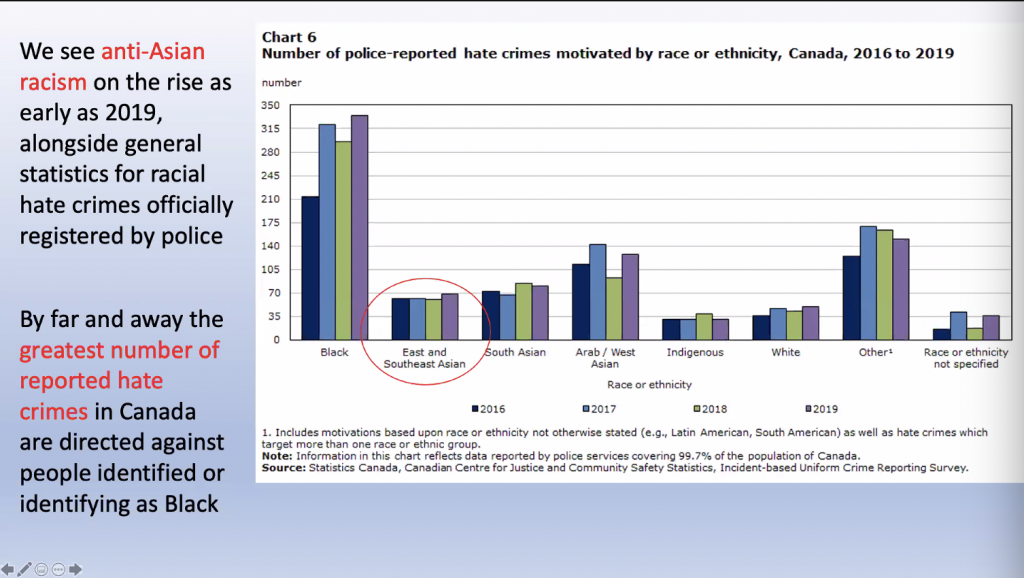

Contrary to stereotypes regarding big cities and main population centers, Muller said the main centers of visible hate are actually in mid-size Canadian cities, with Vancouver topping the list. Anti-Asian prejudice is strong, but anti-Black racism represents the greatest number of reported hate crimes by far, even compared to crimes against indigenous populations, which often top the news.

He concluded by referencing three big “hate” events in Canada this year: Antisemitic and anti-Palestinian hatred and violence in demonstrations across Canada; the murder of three generations of a Muslim family run down with a pickup truck in June; and the discovery of the remains of thousands of Indigenous children at former residential schools.

Q&A

During the question-and-answer portion of the webinar, various topics were addressed by the panelists in connection to questions asked by the audience. Main points included:

- Churches have been on both sides of the issue of structural racism historically. They still have impressive power to bring human rights issues to the forefront of national agendas—and especially since churches in Canada are currently filled with people mainly from Africa and the Philippines, they have even more of a responsibility to be advocates of racial justice.

- The Black church, which is about 200 years old in Canada, has always been a site of social justice for the community and for people as a whole.

- Reporting and statistics don’t currently reflect the intersectionality of hate crimes. Police reporting can only check one box—either Black or Muslim—when a Black Muslim is attacked. So statistics might be inaccurate.

- Addressing inequalities in social class lines and the racial divide in Africa starts with addressing access to education.

- Canadian “Blackness,” which is specific to the distinct experience of people in Canada, often isn’t addressed because definitions and solutions are borrowed from America, and sometimes they don’t apply.

- The goal of inclusion shouldn’t necessarily be to participate fully in current damaging neoliberal, capitalist contexts, but to be included in organizations and think tanks striving for a better, more just world.

- In Southern Africa, the church is often the primary “voice of the voiceless,” standing for social justice and providing necessary health and education services to the public. When churches raise a voice against the establishment, people listen. There is still much hope for what the church can do.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Sibanda thanked the panelists for their diverse and insightful contributions to the discussion and invited all participants to continue following the work of the G20 Interfaith Forum Anti-Racism Initiative.

“Structural racism is the one thread that combines everything we’ve heard today. It provides people with resources, power, and access. It’s divisive, it marginalizes, it dehumanizes. And it needs to be addressed.”